THE GLORIOUS LIFE OF ALFA UMAR IBN SAYYID Part 1

by Shaykh Muhammad Shareef bin Farid

February, Black History Month, affords us to revisit the life of the illustrious and benevolent Turudbe’ Muslim, Alfa Umar ibn Sayyid. Perhaps more than anyone else among the enslaved Turudbe’ Fulbe’ descendents of the Abrahamic line, Umar constitutes the best example of the persistence of an identity construct because of the extensive Arabic writings he has bequeathed to us. There is much controversy connected with him, because the Anglo-American writers have claimed that he had accepted Christianity.

However, when careful examination is made of his writings, the evidence proves the contrary.

Umar ibn Sayyid was born in 1770 in Futa Toro, the original home of the Fulbe’ speaking ethnic groups known as Tukulur or Turudbe’. As he said in his Autobiography: “The place of my birth was Futa Toro (which lay) between the two rivers” 1

This region was for many centuries under the sovereignty of the Takrur, Malian and Songhai empires, respectively. With the Moroccan/Portuguese invasion and sacking of the Songhay empire in 1592, many Turudbe’ speaking scholars took up the banner of jihad and attempted to establish Islamic government throughout the regions of the bilad’s-sudan in general and in Futa in particular.

From 1599 until 1670 the Denianke Fulbe’ ethnicty ruled the area. The spiritual leader at that time was a Qaadiri Imam named Malik Sy. The decline of the Denianke was the result of the European slave trade.

The region of Bundu is the southern most tip of Futa Toro which lies on the west bank of the Faleme’ River. Islamic learning was originally brought into the region of Bundu as well as Niokholo and Dentilia by the Jakhanke’ clerical communities coming from Diakha-Bambukha. 2

The Imam who originally established Islamic learning in this region was none other than the famous al-Hajj Salim Suware’. It is from him and his many students that the transmission of the Muwatta of Imam Malik, Tafseer ‘l-Jalalayn and the as-Shifa of Qadi Iyad were transmitted in the entire region of Futa Toro and Futa Jallon. 3

In the region of Bundu at the central town of Didecoto, reside two grandsons of al-Hajj Salim: Shaykh Abdullah and Shaykh Ture’ Fode where this learning tradition still persist. Later, Futa Jallon became a magnate for learned scholars and Arabic literacy where more than 60% of the inhabitants were versed in the Arabic language. 4

Education in this region was propagated by the famous Saalamiyya families who spread the Qaadiriya Tariqa throughout Guinea, Senegal and Gambia and traced their ancestry to Umar ibn ‘l-Khataab, may Allah be pleased with him.

It was under the shadow of this great reform and intellectual tradition that Umar ibn Sayyid received his 25 years of training and instruction. He began his formal education of memorization of the Quran at age 6 in 1776 and by 1801 at age 31, he had completed an exhaustive and thorough Islamic education.

There is no doubt, when we compare his education with the curriculum laid out by one of his contemporaries, another enslaved Muslim, Lamin Kebbe’, that Umar had reached the level of Alfa or al-faqih (jurist). 5

At this level Umar ibn Sayyid probably returned to his home to teach children the Quran, act as kaatib (scribe) for senior jurist, enhance his knowledge with the senior scholars, enter the higher esoteric training in the Qaadiriyya brotherhood, and assist the Almami Abd’l-Qaadir Kan in the administration of the newly formed Muslim confederation. He said in his Autobiography:

“I was entrenched in seeking knowledge for twenty-five years. I came back to my region and after six years a large army came to our land. They killed many people and seized me bringing me to the great ocean. There they sold me into the hands of the Christians.” 6

When Umar ibn Sayyid was captured at the age of 37, and brought to the United States in 1807, it was the same year that the United States abolished the importing of African slaves from Africa. 7

It was also the same year that the first Muslim slave revolts issued in Bahia, Brazil from Muslims mostly from the same region as Umar. In the same year the regions further east witnessed the major successes of Turudbe’ social reformer and scholar/warrior, Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio. 8

It is clear that the Anglo-Americans did not want in their borders the emergence of the jihads that were engulfing Western Sudan and Bahia, Brazil. The reason for this no doubt is the effect that militant Muslims had upon the African freedom fighters in South Carolina. Among those directly influenced by militant Islam in general, and Umar in Sayyid, in particular, was Denmark Vesey.

David Robertson said in his biography of Vesey:

“The escaped slave Charles Ball, a native of Maryland who wrote a memoir of his South Carolina slavery in 1806, noted the “great many” Africans he had met during his bondage in South Carolina, and that “I knew several who must have been, from what I have since learned, Mohamedans [sic].” 9

The percentage of slaves at least nominally Muslim imported from Africa to the great trading centers such as Charleston has been estimated at 10 percent of the total number brought in during the years 1711 to 1808.

Proportionately, approximately 8,800 of these Muslim individuals must therefore have been sold in South Carolina market in these years. In his decades both as a slave and as a freedman, Denmark Vesey almost certainly knew or observed fellow blacks who continued to practice Islam in their bondage.” 10

Robertson goes on to suggest that Alfa Umar ibn Sayyid, at age 53, was one of the mentors of Denmark Vesey and that perhaps he accepted Islam at his or another Turudbe Muslim’s hand. 11

Like the influence that the Turudbe’ Amir Abd’r-Rahman ibn Ibrahim had upon the revolutionary thinking of David Walker, likewise, the Turudbe’ teacher, Alfa Umar ibn Sayyid, had great influence upon the militant revolutionary, Denmark Vesey. 12

The sense of historical consciousness engendered through the connection with the patriarch Abraham that was transmitted through the Turudbe’ identity concept transfigured the thoughts of Denmark Vesey and gave him the sense of belonging and self-esteem needed to accomplish his revolution.

Herbert Aptheker tells us: “He (Vesey) read to them (his African colleagues) from the bible how the children of Israel were delivered out of Egypt from bondage ”. 13

Thus, the radical intellectual tradition and the militant arms struggle tradition among Africans in America finds its source from the Turudbe’ children of Abraham and their entrenched sense of knowledge of self. Robertson states it more succinctly when he said:

“He (Vesey) was a black man of great physical presence, strength, and intellect, able to grasp the demographic and strategic significance of a black majority in the state, and linguistically fluent and political facile enough to mold various African ethnic and religious groups into one unified fighting force.

From the discipline of Islam he probably took the moral certitude of absolute military victory over unbelievers, just as Africanized Christianity he later publically took the role of a black messianic deliverer.” 14

The Anglo-American writers, both contemporary with Alfa Umar, and thereafter, painted an altogether different picture of the enslaved Turudbe’. He was made out to be docile and compliant to his lot as a slave.

Further, it was stated repeatedly that he had converted from his native religion of Islam. However, the evidence of his own writings prove otherwise.

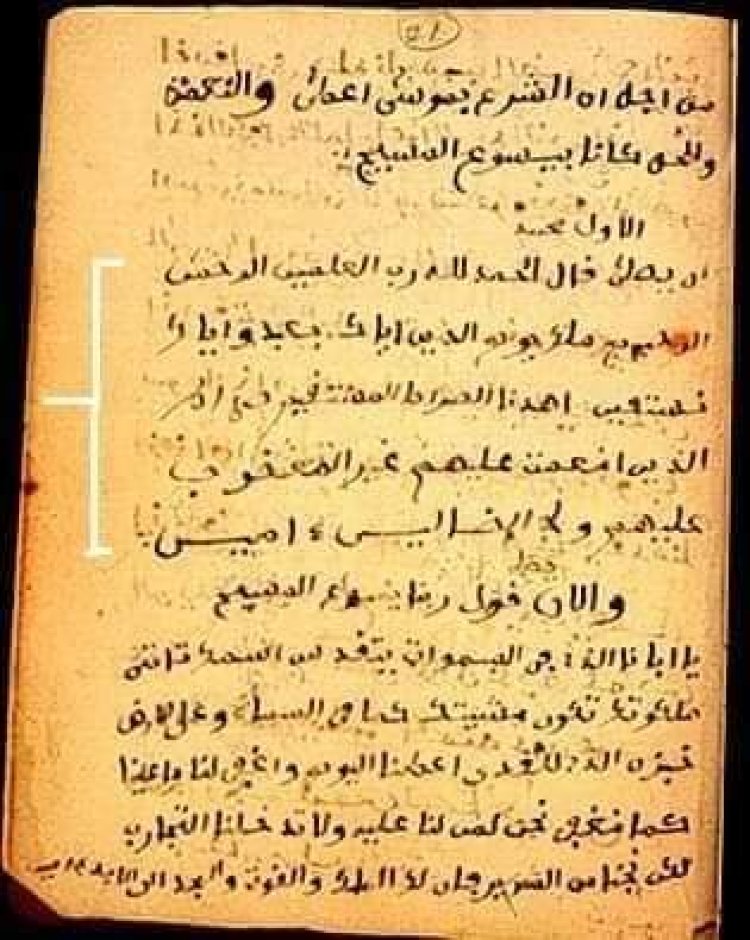

The most astounding evidence for the persistence of Alfa Umar’s belief in Islam was a letter written around 1820 at age 50 where the learned Turudbe’ scholar says at the beginning:

“You show Allah in male or female form? Behold, such is a division! [not clear] These are nothing but names that you have made up, you and your fathers, which Allah did not reveal. All good is from Allah and no other.” 15

Here is a scathing attack, not unlike the criticisms made by Amir Abd’r-Rahman ibn Ibrahim, where Umar assails the Anglo-Americans for their Hellenistic paganism.

He calls them to account for associating deities besides the One God Allah ta`ala. In spite of being under the abject subjugation of the white Christians, yet Umar remained firm on the Abrahamic covenant of commanding all that is good and forbidding indecency.

Umar remained undeviating from the pure unadulterated monotheism that was bequeathed to Abraham, Isma`il, Ishaq, Yaqub and all the their descendent until Muhammad, may Allah bless all of them and grant them peace. Umar said in his letter citing one of the most fundamental verses that established the tenets (`aqeeda) of Islam:

“The Messenger believes in what was revealed to him from his Lord, as well as the believers. All of them believe in Allah, His Angels, His Books and His Messengers. We make no distinction between any of them.” 16

This verse revealed at the end of the second chapter called Al-Baqara (the Cow) delineates the fundamental creed of Islam.

Given Umar’s dept of understanding of these verses along with the causative factor behind their revelation, there can be no doubt that he remained consistent with the fundamental beliefs of Islam; and did not abandon his faith as the Anglo Americans claim.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Umar ibn Sayyid, Autobiography, digital copy of the original Arabic manuscript in possession of author, f 6.

2. Nehemia Levtzion, “Islam in the Bilad al-Sudan to 1800”, The History of Islam in Africa, edit Nehemia Levtzion & Randall L. Pouwels, (Athens, University of Ohio Press, 2000), pp. 79-80.

3. Ivor Wilks, “The Juula and the Expansion of Islam in the Forest”, The History of Islam in Africa, edit Nehemia Levtzion & Randall L. Pouwels, (Athens, University of Ohio Press, 2000), pp. 98-101.

4. Ronald A. T. Judy, Dis-Forming the American Canon: Affrican-Arabic Slave Naratives and Their Vernacular, (University of Minnesota Press, London, 1993), pp. 168-170.

5. Ibid. pp. 172-173.

6. Umar ibn Sayyid, , f 6.

7. Keith Irvine, The Rise of the Colored Races, (New York, W.W. Norton & Company), 1970, p. 75.

8. Muhammad Shareef, The Islamic Slave Revolts of Bahia Brazil: A Continuity of the 19th Century Jihaad Movements of Western Sudan, (Houston, Sankore Institute), 1993, pp. 24-26.; Mervyn Hiskett, The Sword of Truth: the Life and Times of the Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio, (New York, Oxford University Press), 1973, pp. 91-96.

9. David Robertson, Denmark Vesey, (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1999).

10. Ibid, , pp. 37-40.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid. pp. 137-138.

13. Herbert Aptheker, Negro Slave Revolts in the United States, 1526-1860, (New York, International Publishers), 1939, p. 41.

14. David Robertson, p. 39.

15. Allan Austin, p.456. The translation is my own because the translation offered in the text on page 513 is not clear.

16. Ibid. p. 457. Again the translation is my own.

SOURCES:

The Lost & Found Children of Abrahim

The Autobiography of Umar ibn Sayyid