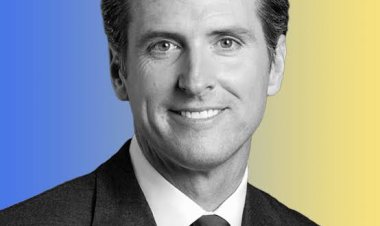

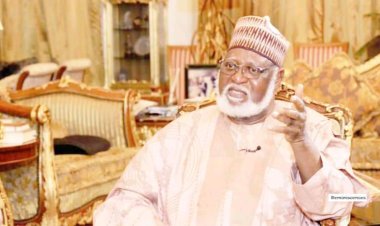

The Day Ironsi Died —Colonel Sani Bello (His Former ADC)

Colonel Sani Bello had a distinguished career in the Military, Diplomacy and Business. In this interview, the 80-year-old former military governor of Kano State opened…

Colonel Sani Bello had a distinguished career in the Military, Diplomacy and Business. In this interview, the 80-year-old former military governor of Kano State opened up on what happened on the fateful morning of July 29, 1966, the day of the bloody counter-coup that overthrew the government of General Aguiyi- Ironsi.

Eighty years ago, it was rare to be an only child; did your position in the family have any influence or impact on the choices you made in life and how you turned out?

I don’t think my being an only child had any relevance to what I turned out to be. This is because although I was the only child of my parents, I didn’t grow up with them. I grew up with my grandparents, who sent me to an Islamic school with other children.

In those days, first children never really related well with their parents because there was a kind of shyness between them. So I didn’t miss that because in my grandparents’ house there were many other grandchildren. And as you know, grandparents tend to treat their grandchildren softly. I enjoyed their love. I had a very good upbringing from my grandparents.

Was this in Kontagora?

Yes. I was there throughout my primary school and part of my secondary school. I went back to my father’s house after I had already developed. I was in Form Three, and by that time I had already formed my own life; so it didn’t have much relevance.

You attended Bida Government College with classmates who later became famous. Out of eight of you, two became heads of state and some became governors. What is special about this group? Was it a coincidence that all of you joined the military and made a big success of it?

I wouldn’t say all of us deliberately wanted to go into the military. When we were in secondary school, I think in Form Five or so, the late Sardauna of Sokoto came to our school, literally canvassing that young men like us should join the army and aim to become senior officers.

Buhari, the military, Ortom: Blood on your hands

Rescue our children, mothers of 6 abducted pupils beg govt, security agencies

He said it was unacceptable to him, and of course, the Government of Northern Nigeria, that we would form 75 per cent of other ranks; not less than 15 per cent of officers should come from the core North.

I think we took that call seriously. As fate would have it, to go to the university in those days you had to go through what they called Higher School Certificate (HSC), and to get that you must sit for a common entrance examination.

Our school was not qualified as a centre for the common entrance exam, so some bright boys were selected. The centre was Government College, Keffi.

Out of 25, 16 or 17 of us were selected to go to Keffi. As we were finishing the exam, the army came. Literally, all of us who went for the HSC exam went to sit for the army examination.

Although not really all of us were serious about the examination, when the result came, it became exciting for us because we found over 1,000 people across Nigeria coming from all walks of life. Some of them came with GCS – six subjects, A-levels. And by that time we had not even done our school certificate examination in 1962.

We were told by the officers conducting the exam that every morning we should check the notice board, and if you saw your name you would go to the paymaster, collect your money and say goodbye. So the challenge was there. So, we went to the board everyday but our names were not there.

There were several events, including medical examinations, physical examinations, written examination and tests, interviews. So, after each of these you go to the board.

Fortunately, almost all of us scaled through. We received congratulations for being accepted into the army. Again, as God would have it, those of us who passed the army examination also passed the HSC examination.

This group became very well known. Do you have a name for yourselves? Are you close to all of them?

We sat in the same class for at least six years, so we must have personal relationships. We have always had a competitive life, so we knew one another very well. Babangida, Abdulsalami, Mogoro, Sani, Nasko and I were close; and we are still close. We are the surviving ones.

Funny enough, those of us who joined the army are surviving. Except two other people, all the rest have died.

After your training at Sandhurst, where were you posted?

After my graduation at Sandhurst on July 29, 1965, I was posted to Enugu. My internal posting in the battalion was operating in Benue. This was during the Tiv riot. After two or three days, the commanding officer would shake your hand and say “goodbye, you have to go to Benue and join your company.”

I went to Makurdi, where I met my first company commander, the late General Gibson Jalo, a good gentleman. He left me in Makurdi for some time. After that, I think Gboko was on fire, so he said I should go there. I spent a month or so in Gboko until things improved.

Aliede was the hottest of the Benue crisis, so I was asked to go there. I was there until January 10, 1966 when the company was supposed to be relieved by another company from another battalion. So we went back to Enugu in January 10, 1966.

So the coup met you on January 15?

Yes, the January 15 coup met me in Enugu. By that time I had spent five days in the battalion.

It was believed that the coup was led mostly by Eastern officers; how dangerous was the situation for you?

When the coup took place, we didn’t know what was happening. First of all, I was a very young and fresh second lieutenant.

Suddenly, we were called together and told that there was a coup, but we didn’t know who organised it. There and then, we were assigned responsibilities. I was assigned to join another company to go and take over the government of Dennis Osadebe in Benin.

The officer commanding the company, Captain Modiebo, who was an ex-Sandhurst too, said we should go and I followed him. He knocked at the door of the premier’s house and a steward came out, dressed in white on white. He demanded to see his boss but he said he was sleeping. He ordered the steward to go and wake him.

Obviously, that was the first time the steward was seeing a soldier in Benin – a tough-looking captain – so he went and called his boss.

He came down after few minutes, looking furious that he was being disturbed. My officer commanding stood up, saluted smartly and announced that he was directed to take over his government. He said, “You must be joking.” But the officer replied that he was not joking, explaining that there was a coup. He was told to look through the window. The premier looked through the window and saw some soldiers with machine guns around and piped down.

“What would you like me to do?” the premier asked. He was told to bring all his ministers so that they would be addressed and given time to vacate their houses. He said okay and started calling them. When they assembled, he told them that government had changed and the military had taken over, so they should vacate their houses immediately. He gave them a short time to leave. There was mass scrambling in Benin for everybody to get out.

I told you that I was a very junior officer, so I didn’t know what was happening. Then, by that time we were settling down to enjoy Benin, suddenly, we received a signal from our battalion from Enugu, ordering us to rush back. We abandoned everything in Benin to go back.

By the time we got to Enugu, we found that the whole battalion was redeployed and mortars were arranged because there was no artillery; everything was arranged and everybody was in trenches. I was not sure what was happening, so we asked.

We were told that we were asked to come back because there were some officers coming with armoured vehicles and there was the fear that they would cut us off and deal with us. That was why they wanted us to come back to reinforce the battalion.

Colonel Sani Bello

Were they against the coup?

No, they were coming to punish Enugu for not participating in the coup and doing what they were supposed to do. Apparently, they wanted us to do some killings there but it was not done. Everything was peaceful in Enugu barracks.

So, because of that, Lagos organisers were coming to Enugu, and that was why our battalion was uncomfortable. We went back and joined the defensive position of Enugu.

The following morning we were told that the attack had failed because they were stopped at Ore and they went back. It was then that we started seeing the kind of coup they organised.

We settled down in Enugu peacefully, but of course we were waiting to hear new orders. We still remained loyal and didn’t do anything in Enugu during the coup.

Loyal to who?

To the central government, not the coupists. It was apparent that the coup would be crushed.

Gen Aguiyi-Ironsi had taken over?

Yes. After we spent few days, the commanding officer took a few of us with him to Benin.

After about a month I was called back to Enugu where I stayed for few weeks before I was redeployed. I was then asked to go for interview to become the ADC to the supreme commander.

Did it surprise you sitting in Enugu, an officer from Niger?

It more than surprised me. I was not in any way qualified to be an ADC to the supreme commander. I was a second lieutenant and they needed a captain, and the one there was a captain. Also, I was in the battalion for less than one year, by all identifications I was not qualified. Shehu (Yar’Adua ) and I were contemporaries.

Was Shehu not a captain by then?

He was a second lieutenant like me. An adjutant, a very powerful person in the battalion, so I wondered why I would be nominated. I went there and they gave me a Land Rover and I headed to Lagos the following day.

When I got to Lagos I went to the Supreme Headquarters, which is the old State House on Marina. I met one Captain Sylvester and saluted him smartly because he was in his final term at Sandhurst when I was going in. And fortunately for me, we were in the same college.

He was surprised to see me. He asked why I was there and I told him I was asked to attend an interview for ADC selection. He said I was late as the interview had been conducted and everybody had gone.

I saluted smartly and said I was going back to Enugu. I don’t know what he thought but he said I should let him talk to the chief of staff. He called the chief of staff on his open intercom and said that one Second Lieutenant Sani Bello from first battalion came for ADC selection.

Ogundipe was a brigadier-general and Sylvester was a captain, while I was a second lieutenant; look at the gap. He said they did not have time for a second lieutenant in that place. I said there was no problem, so I would go back.

I was about to go back, suddenly, Ogundipe called Sylvester and said I should wait. He said he was tired of the first battalion commanding officer because he was not doing the right thing. He said they would give me a docket to take to my commanding officer.

Were they blaming Enugu for sending you?

Yes, I was late. Not only that was I late, a brand new, a second lieutenant was dispensable in the army. After some time he called Sylvester to bring “that officer.” We went and I saluted.

By this time, my legs were shaking. If he gave me a docket, how would I go to the commanding officer and tell him that I received a docket for him from the supreme commander?

What is a docket?

It is like a reprimand. So, I sat down and waited. After some time, General Ironsi came out, spoke something to Ogundipe and they went back to the office. After a few more minutes he called back to say the ADC should bring me.

So I went to his office. As I was entering his office he was looking for something; I don’t know what he was looking for. I later found out that he was reading something, probably something about me. I saluted smartly .

Was Sylvester his ADC?

Yes. He turned to Sylvester and asked if he had shown me my room, saying I would take over from him. He said I should be taken to Madam for introduction and asked if I would be able to start work on Monday. It was a Saturday.

I told him that I came for an interview, which they said had ended before I got there. He, however, said I could come on Wednesday or Friday. Both Captain Sylvester and I saluted and walked out. He took me to Madam.

Was Madam the next important person in hierarchy when you were appointed ADC?

Yes. He took me to Madam and introduced me as Second Lieutenant Sani Bello. He gave me some kind of polish I didn’t deserve to make me look more important. She welcomed me nicely and wished me well.

I went back with Sylvester and he told me what to do and what not to do. I thanked him, saluted and left.

I went back to Benin that Saturday and stayed with Ejoor because he knew me. He asked and I said it went well. From there, I suspected what happened; probably he discussed about me but I was not told. He was a military governor.

So he had spoken to the head of state?

I guess so, I am not sure. The following morning, I went to Enugu and quickly packed my things. After three days I went back to Lagos.

On getting to Lagos I found something that was a little odd. General Ironsi had four ADCs – army, navy, air force and police, and they were all assigned duties.

Despite the fact that I was the youngest of the lot and the newest, I was still given charge of duty.

But did you become the overall ADC or everybody had his role?

I took over, but he was in the role. He got his own assignment, but every time the supreme commander was going out, it was with me.

Were you his official ADC?

I was the one posted next to him in the car.

Looking at it from outside, I am surprised that Ironsi appointed you as ADC, even ignoring the normal processes, why did he do that?

I am more surprised than you, even till today.

Do you think it was an attempt to strike a balance?

I don’t know, but of the four ADCs, one was already a northerner, the police ADC, so it was not necessarily balancing. I don’t know why he picked me.

I must admit that I was the least qualified for the job because I was not ready for it. I was too young. I was only 23 under a unit as an officer and was taking over from a captain. The gap between a captain and a second lieutenant is wide.

How would you describe your experience as an ADC to Ironsi?

It was good but demanding. Ironsi demanded the best because he was very experienced. He was the first and probably the only African officer who worked with the Queen.

As an ADC?

Yes, as an ADC to the Queen. When she was coming to Nigeria, I think he had to stay in Birmingham Palace for some days or months to be trained on the etiquette of being an ADC. So, because of that, his demands were very high. And he was sometimes very impatient. Few times we had some clashes that were not very pleasant to all of us.

Does that mean it was a tough job for you?

It was a tough job.

Were you there on the night of the coup when he was killed?

Sure. After he took over, many events followed. There was something called the May riot, which killed a lot of people in the North, especially the Igbo.

However, peace was later restored. After the riot, things settled down and Ironsi decided to embark on meeting the people; so we came to the North and visited Kaduna, Zaria and Kano.

Didn’t you visit Sokoto?

No. And we were received well in all the places we visited, only one slight incident happened in Zaria – there was an accidental discharge by a soldier, but it was not an issue; it was not meant for us.

After Lagos, things started to slow down a lot more, then Ironsi decided to embark on a tour of western Nigeria.

South West?

It was called western Nigeria, not South West. We went to Abeokuta and everything went well. From there we went to Ibadan, where we met Fajuyi

The governor?

Adekunle Fajuyi, a colonel, was the governor. The three ADCs were there – myself, the air force ADC, Andrew Nwankwo, a lieutenant, then the police ADC, who was a superintendent, DSP Timothy Pam. There was one other person who was never mentioned in that group – Thomas Aguiyi Ironsi.

His son?

The son, who was with us. He came from the United Kingdom on school holidays, so he was to join us on this tour. The reason we went to Ibadan was for Ironsi to address the Council of Emirs, Obas and Obis, who assembled there. The address was to take place on July 29, 1966.

We were hosted to a cocktail by 7:30pm to 8:00pm. We were sent an invitation for that, but on the late minute the general said we should make it between 6pm to 7pm. We had the cocktail, everything went well and we all retired for the night.

Was that after receiving the emirs and chiefs?

No. This was on 28th and the following morning was the meeting of emirs and chiefs.

After we retired, about 12am we started hearing that something was happening. The commissioner of police in Lagos called me to say there was riot in Ikeja cantonment, so I called oga.

On the intercom?

Yes. Later on, the commissioner of western Nigeria called to say there was an uprising. The one in Ikeja was mutiny. Later on, the commissioner of police of western Nigeria called to say there was an uprising in Abeokuta and there were few casualties and I should tell the supreme commander.

I told the supreme commander and he said every one of us should be on uniform.

About that time, something extraordinary happened. After sometime there was a Land Rover coming in but because of where the two superiors were sitting, they could see it.

Fajuyi called his ADC, A B Umaru, to see who was coming in because it was late in the night; and he quickly did that.

A.B. Umaru asked me and Timothy Pam to go with him. As we were going, there was a telephone ringing, so he said we should go back to answer. We allowed him to go because he was used to the house; we were guests. As we were going to answer the phone, there were shots from a submachine gun. Then there was a return of pistol fire. We didn’t know that A.B. Umaru had a pistol in his pocket; then there was a rapid shot of a submachine gun.

We assumed that A.B. Umaru was dead. By now, everybody knew that something was happening.

We were inside the Government House. After sometime we felt like going to see if we could rescue A.B. Umaru in case he had not died.

We went out and met one officer who said they had him. But we did not know what that meant – were they holding him or they had killed him?

Colonel Sani Bello

Were you with Ironsi and Fajuyi in the same place?

No, we couldn’t see them, but we could talk to them because we were at separate wings.

After sometime Fajuyi said we should send for vehicles. We started sending orderlies to bring the vehicles, but unfortunately, the Government House in Ibadan was very badly constructed. All the services were outside the Government House. So, we sent the orderlies, including very old sergeant- major who was very close to Ironsi, and they never came back.

Finally, I decided to go and see what was happening. It was around 7am and I was very unlucky. As I was going out, on reaching the gate, the police that would take us to Mapo Hall where the address of the Obis, Obas and Emirs would take place were coming in as our escort. The coupists assumed that I called them to come and give us support and I came to receive them, so they arrested them with all the dignitaries, including the press secretary.

Were you arrested with them?

I was arrested with them and pushed to the guardroom. It was when I got into the guardroom that I knew what happened. Everybody we sent was captured and detained there, that was why they never came back. So we completely lost information

From the guardroom we peeped through the window and saw General T.Y. Danjuma and one officer, a lieutenant or second lieutenant.

They went to the house and brought out Fajuyi and Ironsi. When they brought them out, they opened the guardroom and asked us to enter the Land Rover. We entered the Land Rover and five of us were driven to God-knows-where. Later on we were told that it was along Owo road.

In the bush?

No, on the road. I called a friend and classmate, the late Ibrahim Umaru, a lieutenant who was in Abeokuta. He was in armoured corp and a very good officer. I told him that it was hot in Ibadan but he said it was hotter there. I told him that I was not likely to stay alive and he said if I could stay alive for the next two hours he would come with his armoured vehicle to rescue me. But I told him that it was too late as I would soon be dead.

We drove some distance. In those days there used to be a small forest along the Owo road on the left. Unfortunately, all the leaders on that convoy were NCOs, no single officer.

Suddenly, the staff officer who was holding a machine gun took an initiative. He cocked it and took a step backwards and put his hand on the trigger. I pleaded that he should not do it there; instead let’s go into the bush. The sergeant-major saw the danger he was facing and said we should go into the bush. We were ushered into the Land Rover again and drove off.

We drove for sometime until we reached a level crossing. We were still moving. I didn’t know whether it was a flyover. When we reached there we turned right into the bush as was demanded by the staff-sergeant. We drove for some distance and stopped.

As we were stopping, as God would have it, Lieutenant Dada, the adjutant of first battalion who I spoke to earlier and who told me to locate Mogoro, decided to come and see what was happening at the Government House.

He went to the Government House and found that it was empty. He asked what happened and I think somebody told him we followed Owo road, so he decided to follow the road and came after us. That delay at the small forest gave him time to cover the distance.

As we were stopping at execution point, Dada was there. We were the same intake and took the same courses in military college.

He ordered Andrew (Nwankwo) and I jumped into his Land Rover, and of course, the sergeant- major started murmuring and trying to disobey, but Dada was a very influential and strong officer.

Specifically, Dada told them to keep the two senior officers and await further instructions, and said we should jump into the Land Rover.

As we were jumping into the Land Rover, we heard a machine gun fire. Dada rushed back. The sergeant-major said “he was trying to run away and we shot him”.

They killed Fajuyi while we were there. I did not see the body but we heard the shot and they told Dada that they killed him. That was the last I heard of Ironsi.

As the ADC, it got to a point where you would either save your life or stay and die with him; was that a choice you faced?

There was no choice; if not that Dada came, we were all going to die.

What about Thomas Aguiyi- Ironsi?

I told you that Thomas was not left alone; he was with a policeman, Timothy Pam. They were the only ones left in the house as he told me later on. He said that after everybody had gone and the place was quiet, he discovered that they were the only two left in the house. He then said to Thomas, ‘We are the only two left in the house, my duty left is to take you back home to your mother but you will do what I tell you to do.”

Fortunately, Timothy Pam was a very experienced policeman. He served in the CID and SIB. He was very experienced in covert operations, so he went to town and brought Fulani dress with hat and glasses; he took one and gave Thomas one to wear and they went to the train station and headed to Lagos. He took him back to Lagos to his mum, and that was the end of the relationship.

Was it a northern coup?

It was.

Were you seen as part of it?

No. I was not part of it nor was I opposed to it because I had no knowledge. I was caught off balance. I heard so many stories, some of them outrageous, including that I had an agreement with my Igbo colleague, Andrew Nwankwo, such that in case it was an Igbo coup he would rescue me, and if it was Hausa or northern coup I would rescue him. But there was nothing like that; we were all looking for survival collectively.

The only person who did not go through the kind of harassment we went through was Timothy Pam, and of course, Dennis Okocha, the naval officer we left at home.

It seems you were part of the coup that overthrew the government of Gowon. And you held Kaduna as the commandant of the 81 Division for the coup that brought in Murtala; is that correct?

It was not possible to hold a coup without involving somebody in Kaduna. While the coup was being planned, I was initially not involved, but later on I was involved. Although I was in Kaduna, my family members were in Ikeja, Lagos and I used to visit them once in a while, especially over the weekend.

Did you sense that something was happening?

No.

I heard it from the airport that I was appointed a military governor and I was supposed to report to Dodan Barracks the following morning.

Do you think it was a reward for your role and link to the relevant officers?

I don’t think there was any kind of reward or link. I think they looked at officers with competence and some kind of qualities of leadership they could rely on.

You were a young man, was it difficult to govern Kano?

It was difficult. My first secretary to the government, Alfa Wali, was helpful but apparently not very popular with the Kano people, especially civil servants. And I don’t know why.

Then I had my brush with Murtala Mohammed, who wanted to strengthen my government.

One of the highlights of your achievements in Kano is the science secondary schools, which helped to bring a new generation of graduates in sciences; is there any other thing you think has been omitted from your tenure in Kano?

Quite a number of roads were built. I was all round, when I came to Kano, fortunately (Audu) Bako has done a lot; he planted seeds of irrigation in Kano State. He had Kadawa Irrigation and Pilot Scheme. He constructed Tiga Dam, but I completed it, he wanted it for the queen, I changed it to something else, he started it, I finished it.

Now, Kadawa Irrigation was a very small scheme. One day, the former agriculture minister, one Bukar Shua’ib came to me and said, Your Excellency, we had a problem with your predecessor.

I asked what problem, he said this irrigation which was started by him, the federal government wanted to take it over, so as to expand it for more value but he refused that it was his project and he didn’t want anybody to take it. I asked why, if you would expand it, who will manage it? He said you. Who share the plus? It’s you. Who will look after (it)? He said you. The only thing we want to do is to expand it for your people. I said he should go ahead. That’s how the Kano West canal came into being. The Kano East canal, I started the Challawa Gorge Dam, which provided water to the Kano East canal. I think we did a lot. We started Aminu Kano Hospital. When we came to government, there was this kind of excitement to take over all missionary institutions, hospitals, schools, so my commissioners came and said we should take over St. Louis, St. Thomas and all missionary institutions and the hospitals. I said no, but they insisted, they said but other states have taken over why not you? I asked them, are we going to pay them compensation or we seize it? They said we pay them compensation. I said if we will pay them compensation, why not build our own and compete with them? I asked how much money you give to these institutions, they said nothing. I said let’s give them some kind of subvention, like St. Louis and insist on a seat in the council and also quota. Then the money we are going to use to pay compensation for schools and hospitals, we go and build our own hospital. So, with that money for the hospital, we build an additional ward in Nasarawa Hospital, and started a clinic which now became Aminu Kano Hospital.

When you retired as a military governor and principal staff officer you became an ambassador in Zimbabwe. That is a bit strange. Did you look for that job; and did you enjoy it?

I didn’t look for the job, it looked for me. Ibrahim Babangida, who had been a very good friend of mine from school, masterminded it.

Was that the beginning of your movement into business?

When I was leaving Harare, Babangida didn’t leave me empty-handed. Although I rebelled against what he wanted, he was very kind.

He appointed me the chairman of Chase Merchant Bank, which later became Continental Merchant Bank. So I didn’t move from Foreign Service to emptiness, I moved to become a banker. That was the best experience I ever had because it opened my eyes from being a routine military officer who could not count more than 10 without my fingers. In the bank, I started learning a little bit of how people were managing funds and resources. It really gave me a good insight into what I wanted to do in future businesses.

You have also done very well in other businesses, including oil and telecom, being the vice chairman of the MTN. Indeed, I saw somewhere in your biography that you have made vast sums of money in business; would you want to speak more about it?

I am not sure about vast sums of money, but I am comfortable.

I am now in the energy sector. That is the only thing I am doing. I am old now, so I don’t want to have any more adventures. I am managing to stay in the power sector for some time, after that I will say goodbye to business and allow the younger generation.

Is part of your money channelled into the Sani Bello Foundation?

Yes; my love is for education. The Sani Bello Foundation helps disadvantaged and young people, women, widows, orphans. We give scholarships and hold annual medical outreaches. This year, we held one on my birthday. So far, we have treated over 5,000 people since we started.

It seems you have no plan to retire.

If I had no plan, retirement will force me to retire. And I think I have retired from the army.

But you have not retired from business yet?

Well, I think I am getting less active now; I am leaving the younger generation to take over the mantle. Fortunately, my sons are doing very well. I have 10 sons and each of them is doing fairly well. So I am very happy. God has been very kind to me by giving me good health, which is the most important thing. I really appreciate that I am still around.

By Daily Trust