Ghana accused of expelling Fulani asylum seekers from Burkina Faso

‘We know we are not wanted in Ghana, but they will kill us in Burkina Faso.’

Ghana accused of expelling Fulani asylum seekers from Burkina Faso

‘We know we are not wanted in Ghana, but they will kill us in Burkina Faso.’

While Ghana has welcomed thousands of Burkinabé refugees fleeing escalating jihadist violence across the border, Fulani rights groups allege that it has also been expelling ethnic Fulani asylum seekers, targeting a community unfairly accused of supporting the insurgency.

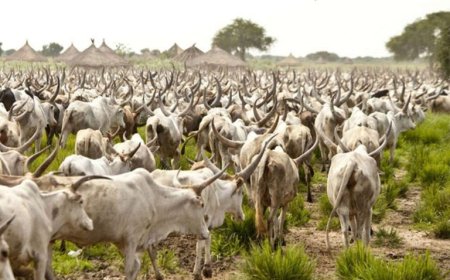

Belko Diallo*, a 45-year-old former herder, is one of thousands of Burkinabé Fulani that the Ghanaian authorities have failed to register as refugees. Instead of being welcomed to Ghana’s Traikom refugee camp, he has had to settle with his family in a hastily erected hut in the dusty scrub land near the northern border.

“When we first heard about Tarikom, we thought – after the Ghana government helped the Mossi and Bissa [their former neighbours in Burkina Faso] – they would help us,” he told The New Humanitarian late last year during the first of two reporting trips. “But after the government took them to the camp and gave them support, the soldiers forced us to go home. You run for your life [in Burkina Faso], then they tell us to return? We cannot return.”

Since early 2022, at least 15,000 Burkinabé have fled into northern Ghana, escaping an escalating conflict between the military, who are backed by armed civilian auxiliaries, and the two main jihadist groups – the al-Qaeda-linked JNIM, and so-called Islamic State.

Across the Sahel, close to four million people have been displaced by the expanding conflict. What began as a secessionist struggle in northern Mali in 2012 has metastasised into multiple interconnected insurgencies roiling both Burkina Faso and Niger. In the past 12 years, at least 42,000 people have been killed, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

In a push south, the jihadist insurgents have also been threatening the coastal West African states of Benin and Togo, and have now arrived on Ghana’s border.

The Fulani ‘security problem’

In what is increasingly an identity-driven conflict, the Fulani – a diverse semi-nomadic community of 30 million people spread across West Africa – are being viewed more and more as a “security problem” by regional governments, Ghana’s included.

Jihadist groups in the Sahel have cannily manipulated local grievances to recruit historically marginalised subsections of Fulani communities. The insurgents have targeted any communities who collaborate with the government, including local Fulani leaders who oppose them.

Malian and Burkinabé security forces – and communal militias with their own local agendas and grievances – have responded with large-scale extrajudicial killings. Fulani communities have found themselves trapped between acquiescing to the militants – on fear of death – and the local militias and military who often believe the canard that all Fulani are jihadist sympathisers.

Ousmane Barry*, an elderly Fulani herder from central Burkina Faso, had moved multiple times to avoid both the jihadists and the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP in French), a civilian militia founded in 2019 to fight alongside the army. In 2020, he arrived in the small village of Siginogo, near the Ghanaian border.

On hearing that the VDP were recruiting in the nearby community of Zekeze in late 2022, he again began to explore the option of relocating. When the bodies of three Fulani men were found by the side of the road in early 2023, he decided it was time to move his family to Ghana.

Source New Humanitarian