Why Ranching Won’t Work In Nigeria Now – Livestock Expert

Muhammed Salihu Ahmad is a livestock expert and retired director in the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. In this interview, the Managing Director of Space Age Continental Investment Limited suggested ways out of the crisis ravaging the livestock sector of Nigeria’s economy.

The issue of grazing routes and ranches has been on for some time now, can you trace its origin in the history of livestock in our country?

Before the colonial masters left, they envisaged that population growth of the country would create challenges in the livestock industry, so they initiated what they called the Grazing Reserve Development Programme. At first, it was called the Fulani Development Initiative.

In 1963, the northern government thought it wise to protect this programme, so it converted forests to grazing reserves and enacted the 1963 grazing reserve law. The law was later modified to incorporate some other things in 1965, thus, the existing status in 1965.

At that time, the northern government had authority over all the lands in the region. And to protect the grazing reserves under that law, they made it mandatory for every Native Authority to employ some personnel who would take care of the reserves and stock routes. In the grazing reserves, they were called grazing guards, while those of the stock routes were called sock overseers. They were employed by the native authorities. Their role was to make sure that people did not encroach into the routes. And they were natives of those areas who knew the location very well and protected it.

After some time, most of them were phased out by natural retirement, death and other circumstances.

Unfortunately, all the tiers of government did not pay much attention to the livestock sector because majority of the budgetary allocation for agriculture would go to crop production.

By the time these people were phasing out, replacement was not made and budgetary allocations were not made to cater for these sets of people. Coupled with the population explosion over the years, people started encroaching into the stock routes and grazing reserves. A lot of the reserves, as at today, have been converted to other uses.

Officially, there are 416 grazing reserves in the country, but in reality, they are not there. There are some grazing reserves that have been converted into university campuses, others into airports. It is state governments that did that. By the time we moved forward and states were created, a lot of issues relating to livestock came up. When the 1978 land use decree was enacted, it vested the power of handling land matters under the state governors.

Then politics came in. By 1979, we started having political patronage because the governors who have the right to allocate lands did it the way they wanted. As a result of that, a lot of them started encroaching into livestock routes. This was because the overseers that were supposed to protect them were not there.

Muhammed Salihu Ahmad

Do you see any possibility of recovering the routes as the president said in his speech?

These routes were mapped out, gazetted and already in existence. The unfortunate situation is that most often, the local and state governments who are the custodians of the land and do not make efforts to see that people do not encroach into it.

People will argue that there is no law that provides for the protection of the routes, but is there any law that provides for the highway in the country? Are they gazetted or protected by any law? It is the government that decided where to float highway.

Most of the routes gazetted in 1965 were mainly in the North, how can this be applied in southern Nigeria?

The president has no control over lands in the country, except the law that gave powers to state governments is modified. Out of the 416 grazing reserves, two are in the southwestern part of the country.

The reality is that if governors in the South were interested in having peace, it does not cost much. For instance, I met the Emir of Katsina in 2017 and we spoke on issues related to conflicts and how it was aggravating. He said he made a rule in his emirate that nobody should cultivate on the right of way. He called his district heads, village heads and ardos and told them that anyone who allowed farmers to cultivate along the right of way would be dethroned. And there was peace for that year. Jigawa State also tried that. This is a very simple thing. It is just the state or local governments that need to institute the law.

This is important because when you have a large herd of animals, their requirement for water is high. It will be very difficult to dig a well, especially in the upper Sahara, which is drying up, to give water to over 200 animals.

It is so funny that some states are saying that with anti-grazing, you can’t move animals on hooves. There are places that are not accessible to trucks; how do you get the animals to the market? We should try to balance it because it is in our interest.

Before now, there were local ways of settling conflicts, and pastoralists have been living with us for so long. Why is it that they didn’t fight? We should ask ourselves.

Recovering some of these routes are becoming difficult and the crises will continue; what other things do you think the government, stakeholders, herders and farmers have to explore?

When President Buhari was elected in 2015, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture was tasked to find a solution to the farmers-pastoralists conflicts. The ministry came back and set up a committee of experts who wrote recommendations for the president. Part of the recommendation is the reopening of the livestock routes. This is necessary because of the two factors I mentioned earlier.

The approval from the president is that they should retrace the routes, and where the routes have been encroached by any infrastructure of public interest, the committee should find a way to reroute them. And rerouting them is not very difficult. If the government wants to build a highway, it will go through properties of individuals and compensate them. This is similar to rerouting.

The economic importance of livestock can’t be underrated. It doesn’t cost much for the government to reopen livestock routes. It is not space-age. All the governors need to do is ask surveyors in the states to open them, and those that can’t be reopened should be rerouted. If we need to pay compensation in rerouting them, we can pay; it is for the economic benefit of the society.

What is your view ranching?

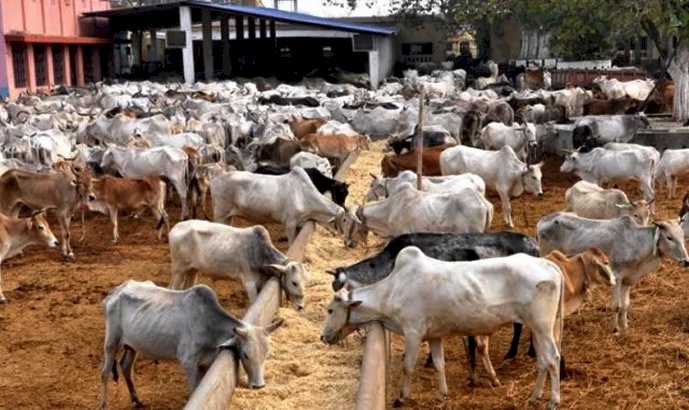

People are talking about ranching but they don’t know what it entails. Ranches are capital intensive. You don’t expect someone with 40 cattle to start building a ranch. For emphasis, to build a ranch that will accommodate over 500 dairy cows will require spending over $400 million. If you need a ranch, the first thing is to acquire a land, enhance it, prepare the land, develop structures, including housing, pasture and water. And there is what we call tropical animal unit, the current capacity of the area.

Each animal requires a certain hectare of land per year. If we are talking about developing ranches for 100 cattle, 200 or 400 hectares of land will be needed. Where do you get the land? Moreover, their movements, in a way, are reducing the level of carbon emission. It was recently discovered that when an animal is concentrated in a place for a long time, it is saturating greenhouse gas, but when they are allowed to move, it is minimising such concentration.

There are many pros and cons of ranching. The reality is that we are not fit for ranching now. What can be done is to encourage the pastoralists to modernise production. What people may not understand is that for the pastoralists, especially the Fulani, their pride is number, not the quality of the herd. We should try to find a way to encourage them to improve the quality instead of the quantity.

How will the ECOWAS free movement of goods and persons affect the cattle routes?

A lot of studies conducted on the movement discovered that a system can’t be changed overnight. Most of the pastoralists across Africa are not indigenous to one place; they move from one place to another. As a result of that, ECOWAS thought it wise to minimise friction as enshrined in its constitution in the free movement of goods and persons, which also considered the livestock subsector. It allows pastoralists free passage across the region, but with a clause that they will have a transhumance certificate. At the point of exit from every country, a paper will be given as a form of identification to allow the person move from one country to another. And it serves as a form of protection for the animals. When the law was formulated, all the heads of government sat down and agreed on the procedure.

There is also the African Union policy for pastoralism in Africa, which is also for movement of livestock.