How Sardauna made me minister – Danburam Jada

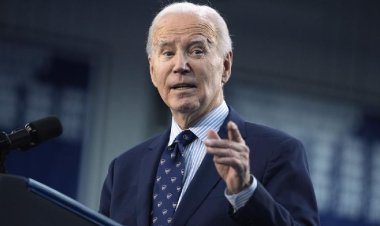

Alhaji Abdullahi Danburam Jada is a rare breed elder statesman who has vast experience in traditional leadership and modern governance. He was an agriculturist, a district head, a First Republic politician, a parliamentarian, a minister, a commissioner, a university pro-chancellor, an anti-corruption tsar – the list is endless. Now 94, Danburam savours his long life. He’s witnessed massive social changes, served in many governments and travelled extensively. A decade ago I attempted to interview him but he declined. My recent effort was, however, successful and I spent hours talking to him at his home in Yola. It’s an informal conversation in Hausa and English. With his advanced age and frail health, there’re things he couldn’t recollect – after all, some of them happened well over 80 years ago, such as the story about a copy of Holy Qur’an his father gave him, which he still keeps – but his brilliant mind flashes throughout our discussion. He would use few words to answer a question and then, after a long silence or interruption, he would remember something and take us back to it. They’re not unbroken narratives for the Question-and-Answer format we normally use in our Reminiscences series. So we use a different style, incorporating background details and historical context from our own research.

Sixty years ago the Nigerian Citizen – the forerunner of the New Nigerian – published a profile of Danburam Jada highlighting how he “shines in farm” and in Parliament. “Abdullahi Danburam Jada, Minister of Animal Health and Northern Cameroons Affairs,” the piece begins, “is the handsome agriculturist, who came to political limelight only in 1956 when he won an election to the Northern House of Assembly on the platform of the Northern Peoples’ Congress (NPC)”. He is “anti-sports” but a “good debater”, the paper claims. “Before becoming a Minister, Danburam was regarded as one of the most intelligent debaters in the House” – skills that probably helped secure him the ministerial post. “As a Northern Cameroonian,” the paper continues, “he would know better of the difficulties of his people and how to solve them”. He is, it says, “the right man in the right place”.

That was in January 1958, when Nigeria was under colonial rule and his own district Jada (in the then Northern Cameroons) was part of the United Nations Trust Territory being administered by Britain. The paper’s assertion regarding his knowledge of his people was about to be tested. Yes, he was the District Head of Jada and had won an election, but the task ahead was much bigger: turning Northern Cameroonians into Northern Nigerians. He would surely need all his skills to get Northern Cameroons become part of Nigeria. “It’s a huge task since there’re some people who were opposed to it,” he tells Daily Trust on Sunday.

Aware of this, and given the ethno-religious complexity of the area, Danburam supported the option of achieving this goal administratively, which Britain had apparently preferred. He pursued a campaign of having the United Nations integrate Northern Cameroons with Northern Nigeria without resorting to a plebiscite that some pro-Cameroon activists were advocating. Cameroon’s historian Bongfen Chem-Langhee, citing UN documents, reported that a United Nations Mission had recommended integration without a plebiscite and that Danburam had supported it.

The UN records show that on 25 February 1959 Danburam told a meeting of the United Nations Trusteeship Council in New York that “there was no need for further consultation on the question of the integration of the Northern Cameroons with the Northern Region of Nigeria when Nigeria became independent on 1 October, 1960”. He argued that Nigeria-Cameroon border was a colonial creation that divided the old Adamawa Emirate. He said “for very weighty reasons of history and geography, and of close ethnic and cultural ties with the people of the Northern Region of Nigeria,” Northern Cameroonians believe that “their true destiny” lies in joining Nigeria. “It was accordingly a matter of vital importance to the people of the Northern Cameroons that they should remain with the Northern Region of Nigeria”. Separating them from Northern Nigeria, he maintained, “would be a direct negation of all the principles for which the United Nations stood”. It was a brilliant argument he presented to the Council but it couldn’t survive the Cold War politics raging then at the United Nations.

Wake-up call

Britain applauded Danburam and vigorously pursued the suggested option at the Council but the Soviet Union blocked it. Eventually, the United Nations had to conduct a plebiscite in November 1959, giving Northern Cameroonians a choice of either joining Northern Nigeria or making decision later about their future. They chose the latter.

It was a disappointing result ffor the pro-Nigeria campaigners, but it also served as a wake-up call for Danburam, his party NPC and their leader Sardaunan Sokoto Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Premier of the Northern Region. They had to re-strategize and prepare well for a future plebiscite. And so when another plebiscite was conducted in 1961, this time giving Northern Cameroonians a choice of joining Nigeria or Republic of Cameroon, the outcome was different. Northern Cameroonians voted (146,296 to 97,659) in favour of joining Nigeria. And the area formally became part of the Northern Region in May 1961.

Southern Cameroons, on the other hand, chose to join the Republic of Cameroon by a vote of 233,571 to 97,741. They have since regretted their decision, and are now fighting to become an independent country called Ambazonia.

Danburam doesn’t seem surprised by the turn of events. He says their decision to join Cameroon was a mistake. They could have probably secured a better deal in Nigeria, given the common colonial language (English) and administrative experience. Southern Cameroons, like its Northern counterpart, was governed by Britain almost the same way as the whole of Nigeria. Integration with French-speaking Cameroon is problematic – but so is splitting from the country, now that they have been part of it for decades. Danburam tells Daily Trust on Sunday that it would be difficult for the English-speaking Cameroon to attain the sort of independence they crave. “Who will give them?” he asks. “It is not that easy”. But he frowns at the on-going violence and wants the conflict to be resolved peacefully.

Relations with Cameroon’s Ahidjo

French-speaking Cameroon had fought hard to secure both Northern and Southern Cameroons during the plebiscites. Their then President Ahmadou Ahidjo had funded pro-Cameroon campaigners on both territories but still lost Northern Cameroons to Nigeria. He was not really contented with getting only Southern Cameroons, even though it had larger population; he wanted both. Historian Bongfen Chem-Langhee said that after Northern Cameroons voted in favour of joining Nigeria, “the Cameroun Government was unhappy and even challenged the conduct of the plebiscite both at the United Nations and at the International Court of Justice”. They were unsuccessful. President Ahidjo accepted reality and opted for a cordial relationship with Nigeria.

Danburam didn’t underrate the late president’s skills. He says the late Ahidjo was a clever politician who quickly recognised the importance of Nigeria. He says after losing Northern Cameroons to Nigeria, the Cameroonian president maintained friendly attitude towards Nigeria, inviting its officials to attend events in Yaounde or Garoua. When the civil war erupted in Nigeria barely six years after the plebiscites, Ahidjo supported the Federal side (Nigeria), even though Cameroon’s former colonial master France was backing secessionist Biafra. “We had a healthy relationship with him (Ahidjo),” Danburam says. “I visited him with Dan-Masani (Late Dan-Masanin Kano Yusuf Maitama Sule) as a Nigerian delegation, and he gave us a very warm reception. Dan-Masani was delighted”.

Dan Masani and Abubakar Imam

His mention of Dan-Masani brought for him some fond memories of the veteran politician, and he immediately turned his attention to him. “Dan-Masani was a very good man and very funny, too,” he smiles. “He’s my good friend.” the late Maitama Sule, a former Nigeria’s Representative at the United Nations, was Danburam’s contemporary in politics. They worked together in the struggle for Nigeria’s independence, attending several conferences. They were both lawmakers under NPC, though Danburam was in the regional assembly and Dan-Masani in federal parliament. They also served as public complaints commissioners during Murtala/

Obasanjo administration. When Maitama Sule died last July Danburam was unwell at the time, but he still wanted to go to Kano for his funeral. “I feel sad I couldn’t go to his funeral,” he says. “I will still go to Kano and express my condolences to his family”.

Another person Danburam fondly remembers is the late Abubakar Imam, the celebrated writer, first editor of Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo and author of several Hausa books. Imam was much older than Danburam but they had worked together in the NPC and Northern Region’s government. When Danburam resigned as minister on 1 October 1960 due to the temporary separation of Northern Cameroons from Nigeria as the result of the latter’s independence, Sardauna appointed him as a part-time commissioner in Northern Nigerian Public Service Commission. And he became a full-time commissioner after Northern Cameroons joined Nigeria. It was in the commission that he worked with Abubakar Imam, who was its chairman. He says the late writer was a man of great intellect and wisdom. “He knows his work very well and is fond of using proverbs,” Danburam recalls.

No favouritism

There had been claims of appointments of unqualified Northerners to fill posts in the region as part of Sardauna’s ‘Northernisation’ effort. Danburam disputes this. Contrary to claims of favouritism in employment in the civil service, he says appointments were actually based on merit. No bias also against any section of the North, he stresses. There were equal opportunities for all Northerners, regardless of their socio-economic and religious backgrounds. “We don’t favour anybody. People get jobs on merit,” he says. “When you finish your studies, you would apply for the job you like. We would look at your competence and give you the job, if you’re qualified”.

The emphasis, he says, was on competence, and that was why things worked well at that time. The former premier, he maintains, focused his attention on manpower development. Provision of education and training and re-training of staff were key part of his programmes. “We would visit many places to recruit qualified people to work in various sectors,” he adds.

It was the same approach he transferred to the North-Eastern State after its creation in 1967 when he became the pioneer chairman of its public service commission in 1968. He says students from the region who studied in various parts of the country and abroad were encouraged to return home and take up relevant roles to man the region. He says he would lead his team to many places to conduct interviews as part of the recruitment drive.

Danburam also took to the commission the same culture of transparency and incorruptibility he had adopted while serving in Sardauna’s government. He built the commission on an excellent footing and was reputed to have fought a relentless war against corruption and nepotism. “The story of his refusal to sanction the employment of an unqualified relation of his is now legendary,” a citation on him by Bayero University Kano (BUK) said when the university honoured him with a doctorate degree in 1989. “Consequent upon carving for himself the image of a moral crusader in an age of moral decadence, Alhaji Danburam was invited by the reformist regime of General Murtala Muhammed to assume the post of Public Complaints Commissioner in the North-Eastern State and subsequently for the new constituent states of Bauchi, Borno and Gongola states from November 1975 to October 1979,” it added. He held the post for two more years in his then Gongola State before retiring in November 1981.

Nine months later, despite his protests, he was recalled to serve again, first as a member of Bayero University Governing Council and later as the council’s chairman and pro-chancellor. After spending about four years there he was appointed Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of Usman Dan Fodio University, Sokoto, in 1986 – a post he held for years. He was also a member of many boards, including Northern Nigerian Scholarships Board, Police Selection Board, and Regional Committee of the West African Examinations Council (WAEC).

A summon from Sardauna

Danburam’s biggest break was his ministerial appointment, and apparently it was the one that surprised him most. He had no prior knowledge or hint that he was going to be made a minister. He was in his hometown of Jada where he was serving as its district head when he got a call. It was an urgent call and so he had to attend to it. “When I received the call, I went to Lamido (the then Lamido Adamawa Dr Aliyu Musdafa) in Yola, and he said, ‘Well, the call is from Sardauna. He is the one looking for you’,” Danburam says. “I expressed my surprise but he said, ‘Well, go and see him. The message is from him’”. Danburam was very close to Lamido Aliyu Musdafa (the father of current Lamido Adamawa Dr Barkindo Aliyu Musdafa). They had known each other since childhood, and it was Lamido who appointed him the District Head of Jada in 1955. He was only two years into the post when this call came. He was also a member of the Northern House of Assembly. At that time traditional rulers were not barred from politics. He was only 33 and was contented with his two posts. But unknown to him, the Northern premier had prepared bigger roles for him. When he reached Kaduna and met Sardauna, he got an excellent reception. Sardauna told him of the appointment. It’s a huge promotion. He did lose his title of a district head but he became the minister for animal health and forestry and Northern Cameroon affairs.

There was no lobby, no political manoeuvre, no crowd renting, not even an expression of interest. He was simply offered the post. “I wasn’t looking for it,” Danburam says. “I didn’t even know there’s such a plan.” His talents were spotted and he was appointed on merit. His academic and occupational backgrounds have been in agriculture. He had attended School of Agriculture (renamed College of Agriculture, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria) and worked in the same field for eleven years. And he was a traditional ruler from the Northern Cameroons, an area Northern Nigeria was keen to get. With those fitting backgrounds, the premier apparently felt that Danburam was the perfect person for these portfolios. But even before the appointment, Sardauna had apparently noted Danburam’s excellent debating skills in parliament, as the Nigerian Citizen’s article has suggested.

How we handled herders-farmers problem

As minister for animal and forestry, Danburam had to deal with the issue of relationship between herders and farmers, and he could still remember some of the measures he took in that respect. He says first there were cattle routes, which greatly helped minimise areas of clashes between the two groups. And then there was effective monitoring by the government, which aided early detection of problems. He admits that even at that time there were cases of misunderstanding and conflict. But the government was up and doing, and never allowed things to degenerate. “Once we notice a potential area of conflict, we would involve traditional rulers to intervene quickly and address the problem,” he says. “We never allowed things to get out of hand.”

He believes that involving traditional rulers could still help in addressing the current herdsmen-farmers conflict. He wouldn’t want to be drawn into the politics surrounding it but he is clearly unhappy with the violence associated with it. Perhaps because of his experience as a former district head, Danburam puts great emphasis on the relevance of traditional rulers in conflict resolution. “They know their communities and could help in resolving many conflicts,” he suggests. He apparently blames a lack of continuity in governance for those problems that seem to have followed the demise of Sardauna.

How soldiers stopped Ribadu after Sardauna’s killing

The late Ahmadu Bello was a remarkable personality Danburam had great admiration for. And so the way he was killed in a violent military coup in 1966 upset him very much. “I was in Kaduna and it was a shocking experience,” he pauses. “Top government officials were all coming to my house”. There was a long silence and then he continued. “We all sat in my house to figure out what we would do,” he says. “It was a period of sadness all over the city”. His house became like a rallying point for the government functionaries, but with merciless gun-wielding army officers taking control of the government, there was apparently nothing they could do beyond grieving. They all went and participated in the premier’s funeral prayer, he says.

It was a painful experience and he doesn’t seem keen in talking about it. He does, however, briefly recall the experience of his close friend, the late Ambassador Ahmadu Ribadu, the father of former Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) Chairman Malam Nuhu Ribadu. Danburam and Ribadu had a tight relationship. They were in the same age group (Danburam a year older), were both in the NPC and had both worked in building the party in the Adamawa Emirate – Ribadu was at that time a member of the Federal House of Representatives in Lagos. Sardauna was their leader, whom they both revered. Apparently, Ribadu was on his way to Kaduna on the day (or not long after) Sardauna was killed. And he was stopped by soldiers as he tried to enter the city, Danburam recalls. “They told him that it would have been safer for him to stay where he was than to come to Kaduna at that time,” he says. “He’s coming to my house. They insisted that it was also safer for him to stay with them than to enter the city”. Danburam couldn’t recollect all the details of his friend’s encounter with the soldiers, but apparently Ribadu did eventually make it to his (Danburam’s) house safely. “He didn’t find it easy,” Danburam says. There was a long silence as he tried to remember something and then gave up. “He was my very good friend,” he says of the late Ribadu, “a nice man”.

Father’s memorable gift

One other thing Danburam could still remember briefly was the gift of a copy of Holy Qur’an that his father bought for him well over 80 years ago. He still has it with him and clearly loves it greatly. His father sold some of his cows to buy it for him, he says. The study of Qur’an and acquisition of Islamic education as a whole came top right from his childhood. Danburam didn’t start any form of Western education until after he’d studied the Qur’an and many fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) books. He entered Yola elementary school at the age of 13 and still continued with his Islamic education. This apparently enhanced his performance in the Western-style schools and earned him accelerated promotions. Within three years he had completed his primary education and been admitted into the famous Yola Middle School, which he completed in less than four years. Renamed General Murtala College, Yola Middle School was the breeding ground of Adamawa elite. Among its former students were the late Lamido Aliyu Musdafa and former Secretary to Gongola State Government the late Hamidu Alkali, Danburam’s classmate. Its other former students who later held public offices include former Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) Chairman Bamanga Tukur, former Chief of Air Staff the late Air Marshal Ibrahim Alfa, former Petroleum Minister Professor Jibril Aminu, former Adamawa State Governor Murtala Nyako, former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, and many more.

In school, Danburam was good with maths and other academic subjects but sport, as the Citizen says in its piece, was not his passion. Walking is, however, among his three hobbies – the other two being reading and listening to radio. But right from young age, Danburam’s charisma and leadership qualities were unhidden. They became so obvious at the Yola Middle School he was appointed its head-boy. After leaving school he joined the Native Authority as an agricultural assistant and later a supervisor of agriculture, following his studies at the School of Agriculture, Zaria. He was a vice-chairman of NPC in Yola before he won his parliamentary seat and later became a minister. His subsequent accomplishments show that it was not only Sir Ahmadu Bello who recognised his talents, the British establishment, too, did. Queen Elizabeth II honoured him with an OBE (Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in January 1963 for his public service. And the Federal Government bestowed OON (Officer of the Order of the Niger) honour on him. It’s in an effort to sustain his legacy that a foundation (Abdullahi Danburam Foundation) was registered in 2012.

A family man, Danburam never compromises on the training and proper upbringing of children. Two of his sons (Mohammed Gidado and Abubakar Baba) had died, but he has 15 grown-up children (Aishatu Charo, Sakinatu, Dr Nafisatu, Umaru Sahabo, Ahamdu Tijjani, Usman Nanu, Aliyu, Ibrahim, Fadimatu, Amina, Hamidu, Muhammad Aminu, Zainabu, Mahmud and Mohammed Dahiru) who are all doing well in their respective capacities. He also has 55 grandchildren and 49 great-grandchildren. But it’s not only his decent family life that endears him to many, it’s also his uprightness and modesty. They’re the recurring words used to describe him by the universities (the BUK mentioned earlier; Federal University of Technology, Owerri; Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria; and Usman Dan Fodio University, Sokoto) that conferred honorary degrees on him. The BUK citation in particular describes him as the “paragon of Fulani modesty, self-denial and self-sacrifice”. It is testimony to that modesty that even this interview he wasn’t really keen to grant. Danburam cherishes a quiet, simple life.